What is new with the European machinery directives?

The EU Machinery Directives are currently being superseded in favour of the Machinery Regulation, which comes into force in January 2027.

The European Union (EU) has for over three decades legally mandated that any product sold there be compliant to all relevant directives. These directives are in place mainly to ensure the safety of the product. The CE marking on a product is used to indicate that it complies with the directives, giving assurance about the product to the consumer.

The European directives, while not mandated here in Australia or New Zealand, are still highly relevant for us. Exporters of industrial machinery into the EU will need to be acutely aware of the directives, as their products must strictly adhere to them. Similarly, many of the products that we import from Europe will most likely have the CE marking, confirming their compliance to EU directives.

It’s therefore vital that we’re aware of any amendments to these directives, especially major changes. For the case at hand, we’re currently in a transition phase, where the existing Machinery Directive 2006/42/EC, which has been in force since December 2009, is being phased out. Its replacement is the Regulation (EU) 2023/1230 of the European Parliament and of the Council of Machinery. This regulation was first published in June 2023 and will become law in all member EU states on 20 January 2027. A 42-month window was given for relevant parties to become compliant, but the deadline is now less than 18 months away.

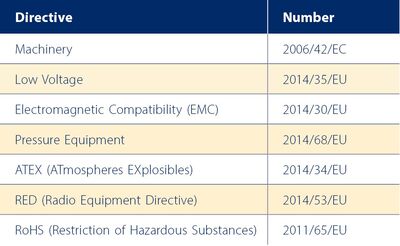

It’s important to note that multiple directives will often apply to a machine being sold into the EU, not just the Machinery Directive/Regulation. While the complete list of applicable directives will depend on the machine type, those listed in Table 1 give an idea of what’s required.

What are directives and why have them?

‘Directives’ within the EU are akin to policies that are legally enforceable and they are common to all the member states. Directives seek to provide assurance that products meet all the various health and safety requirements of the EU, as well as environmental concerns and energy efficiency levels mandated by the EU.

The implementation of consistent directives across all member states has had numerous advantages: it has provided cohesion across the EU and provided a means of implementing common policies, such as safety for workers and environmental protections. This allows all member states to work towards common objectives.

Consistent directives also encourage commerce within the EU, by removing trade barriers. It makes the EU a single market and encourages the free movement of goods between countries. Similarly, those who export machinery into multiple European countries only need to contend with one set of regulations. This will ultimately lead to increased competition from international sources.

Legal certainty is also provided across member states by having a single set of rules to abide by, which is important for maintaining consumer rights.

From ‘Directive’ to ‘Regulation’

Given the significant advancement in technology since 2009, it’s hardly surprising an update to the Machinery Directive was deemed necessary. The new Regulation seeks to increase safety and address numerous shortcomings in product coverage and conformity assessment procedures that became apparent with the Directive.

While the thrust of the Regulation remains the same, its application area has been extended to include machinery and “related products”. It has been lengthened considerably and contains almost double the number of articles. The content has also been reorganised and expanded where deemed necessary.

But perhaps the biggest single difference is the change from a ‘Directive’ to a ‘Regulation’. The main difference is that directives only set out goals that need to be achieved, which still allows individual countries to formulate their own national laws to apply them. This has led to some divergence in interpretation and variances in laws between the states.

‘Regulations’, on the other hand, must be transposed verbatim into national law by each country, making them legally binding. There is no possibility for amendments, meaning one consistent law throughout the EU.

What is new?

We will now briefly look at some of the changes that will be ushered in by the new Machinery Regulation.

Clarification of definitions

There were some legal ambiguities due to the lack of clarity on the scope and definitions of certain terms in the Directive, leaving open the possibility of safety gaps. Below are some of the terms whose definitions have been reworded.

Safety components have been identified as being either a physical component (hardware) or digital (software) or a combination. Software implementations can now also be recognised as a standalone safety product.

The term ‘substantial modification’ of a machine has been clarified to mean if new hazards are created, or if its existing safety concept is inadequate. These modifications can also be software-driven. In these cases, the machine must undergo a renewed risk assessment and safety audit.

An ‘authorised representative’ has been defined as a person or legal entity that represents the manufacturer in the European market. The role includes being the provider of documentation, such as the Declaration of Conformity (DoC), manuals, test reports and the CE mark. However, design-related work cannot be completed by the authorised representative.

Specific roles have also been assigned to ‘economic operators’, namely the importer and distributor of machinery. They are given extensive obligations for the health and safety of machinery users. If a product has no authorised representative, then economic operators must assume responsibility for providing documentation and product tracing, for reportable safety issues.

Strengthening machinery type classifications

A formalised definition of ‘machine’ has been established, allowing segregation into two groups, depending on hazard levels. These categories have been considerably strengthened to clarify the need for inspection.

The Regulation works with the New Legislative Framework (NLF) for its conformity assessment procedures. The NLF uses a modular approach to determine how products are to be assessed. Modules A and C allow self-assessment, whereas Module B must involve a notifying body for certification. Module H and the new Module G are for higher-risk products, requiring more rigorous testing by third parties.

Software‑driven, emerging technologies

The Machinery Directive understandably didn’t cover the risks that could stem from emerging technologies, especially those that are software driven. But software-implemented functionality is now far more prevalent, so the Regulation has been expanded accordingly.

The term ‘AI’ (artificial intelligence) isn’t specifically mentioned in the Regulation, although the expression “fully or partially self-evolving behaviour using machine learning approaches” is used when categorising machinery. Risk assessments must include hazards that could be generated by any self-evolving behaviour during the life cycle of the machine.

AI can be used for functional safety but needs to be accompanied by established safety measures to mitigate potential risks. Conventional safety must still be able to override AI functionality.

Industrial security has become an integral part of machinery and thus the Regulation includes new sections covering ‘protection against software corruption’. It mandates that every intervention with the machine’s software, be it legitimate or illegitimate, be recorded as evidence and that these records be kept for at least a year.

Furthermore, machinery must be reliable enough to “withstand malicious attacks from third‑parties”. These cybersecurity attacks must not lead to hazardous situations. The machine must also be protected against data corruption, be it accidental or intentional.

The Regulation is always looking to harmonise with other standards. Two candidates relevant to security are the European Cyber Resilience Act (CRA) and the Network and Information Systems (NIS 2). Both were adopted by the EU in October 2024, but neither has yet to be formally harmonised into the Regulation.

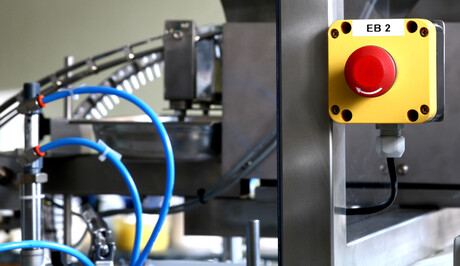

Testing of safety functions

A ‘safety function’ is defined as a function that serves to fulfil a protective measure designed to eliminate (or at the very least reduce) a risk, which, if it fails, could increase that risk. The Regulation stipulates that a safety function in a machine should, where possible, be testable by the end user. The manufacturer is to provide descriptions for test procedures, as well as adjustment and maintenance for safe usage.

Softcopy documentation is now acceptable

Machines can now be delivered with digitised documentation only, according to the Regulation. This includes the EC Declaration of Conformity. Online access can be via a barcode on the machine and must remain available for a minimum of 10 years.

This long-awaited change has been brought about for environmental and monetary reasons. Paper-based documentation must still be freely available on request for the first month, after which it may become a chargeable item.

Additional material in the Regulation

The Regulation has been expanded to include autonomous mobile machinery, reflecting increased use by industry. It states a risk assessment must be done for the areas where autonomous vehicles operate. There also needs to be a defined supervisory function specific to autonomous mode, and safety functions that perform independently of the supervisory function. Failure of the steering system cannot impact on safety.

CE marking

‘CE’ stands for Conformité Européenne, which translates to European Conformity. CE marking is not a product standard, but a label of conformity for products supplied into Europe. When affixed to a product, it signifies that it complies with every single EU directive that applies to that product.

In the case of machinery, it’s normal that numerous directives will apply, including the Machinery Directive. There are also some very general directives, such as Units of measurement (80/181/EEC), which stipulates the use of SI units and precludes the usage of non‑metric components in machinery.

It’s important to note that the CE mark was never intended to be an indication of the quality of the product, nor can the country of origin be determined from CE marking. CE merely signifies that it meets European standards.

Compliance to CE marking is enforced by all the EEA member states. Government authorities can at any time request to see supporting documentation and can even request samples to conduct lab testing. If a product is found to be non-compliant, it will be withdrawn from the market and the manufacturer or distributor face penalties.

Conclusion

All machinery sold into Europe has, for the last three decades, needed to comply with the Machinery Directive. This Directive is currently being superseded in favour of the Machinery Regulation, which comes into force in January 2027.

European directives are not mandatory in Australia, so the impact will be indirect but still significant. The primary aim of EU directives is to ensure product safety for users, with product compliance being confirmed by a CE mark being affixed to that product.

Reference

European Commission 2025, Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs: Machinery, <<https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/sectors/mechanical-engineering/machinery_en>>

|

Integrating standard signals into functional safety

Non‑binary signals such as analog inputs and encoder readings are very common and should be...

Light curtain or safety laser scanner?

Safety light curtains and safety laser scanners are the two most common machine protection...

SIS logic solvers: more choices are needed

Most safety applications can be handled by safety PLCs; however, they are frequently overkill...